This month Nigel Akehurst visits Hiltonbury Jerseys on the outskirts of Winchester, Hampshire, to meet tenant dairy farmer Oliver Neagle. Over two decades, he and his family have transformed their business from a precarious tenant operation into a thriving diversified enterprise, adding value, selling direct and building strong connections with customers.

It’s late morning as I arrive at Attwoods Drove Farm. Parking up in front of the farm shop and milk vending machine, I am greeted by dairy farmer and entrepreneur Oliver Neagle, who had just finished a chat with a regular customer stocking up on raw Jersey milk.

“Each week we sell around 400 litres of raw milk and another 400 litres of pasteurised milk direct to customers,” said Oliver proudly. “The vending machine and shop are the beating heart of what we do now.” His wife Shaleen manages the shop, which also stocks their own beef, homemade fudge, their own natural soap made with raw milk and their famed Hiltonbury Jersey ice cream. Yet this bucolic farm scene didn’t emerge overnight.

From drum kit to pedigree jerseys

Sitting down for a chat over a coffee, Oliver explained that his own farming journey began over two decades ago. At the age of 31, he sold his beloved drum kit – the only thing of real value he owned – to raise £900 for two Pedigree Jersey show cows, Hiltonbury Yarrow (Yarrow’s head is the current herd logo) and Hiltonbury Yuletide.

“I wanted to carry on our herd name after mum sold up,” he explained. “Those two cows cost £450 each, and the only way I could get the money was by selling my drums.”

His family had farmed locally as tenants for generations, but this move marked the beginning of a new chapter in Oliver’s farming career after working throughout his twenties for agricultural contractors in Somerset.

Today, Oliver keeps around 300 Jerseys, primarily home-bred, and milks about 120 at any given time. The rest are followers, replacements and a growing number of beef crosses that are sold through the farm shop.

The challenges of tenancy farming

As a tenant farmer working with Hampshire County Council, Oliver’s path has never been straightforward. Over the years he moved three times, never certain when the council might need the land back. He spent 16 years at a holding in Botley with a rundown parlour, which made planning for the future very difficult.

“Dairy’s a long-term game,” he said. “You’re always thinking years ahead, but we never knew when we’d have to move on.”

Eventually, a prime site closer to Winchester became available. Oliver seized the opportunity, negotiating a deal that let him design a modern dairy unit on council-owned land. The council invested around £1 million and Oliver added £250,000 of his own, installing a 24:24 Dairy Master parlour and improved infrastructure for silage clamps, young stock housing and a workshop.

“We moved the cows here five years ago,” he said, gesturing to the modern buildings. “It’s made a world of difference; cut milking times, improved cow comfort and given us a proper base from which to diversify.”

Going direct – the milk vending machine

Oliver’s first major step into direct sales came in 2016 at the old Botley farm, when he placed a milk vending machine inside a lorry container. “I think I was the first in Hampshire with a vending machine,” he said. “At first, it was just testing the water, but people loved it. They drove from all over, and that’s when I knew we were onto something.”

Now, the vending machine sits in a permanent building outside his farmhouse. Customers come for a couple of bottles or sometimes 50 or 100 litres at a time. Raw milk and pasteurised milk fans are both catered for. This direct approach lets Oliver set his own price, providing vital daily cash flow.

“Without these changes, we wouldn’t be here,” he said.

The farm shop and adding value

Keen to build on this momentum, Oliver and Shaleen established a farm shop in an existing building on the site, open seven days a week. Shaleen runs it at weekends, the busiest times, while during the week customers use an honesty box, knowing the family is never far away.

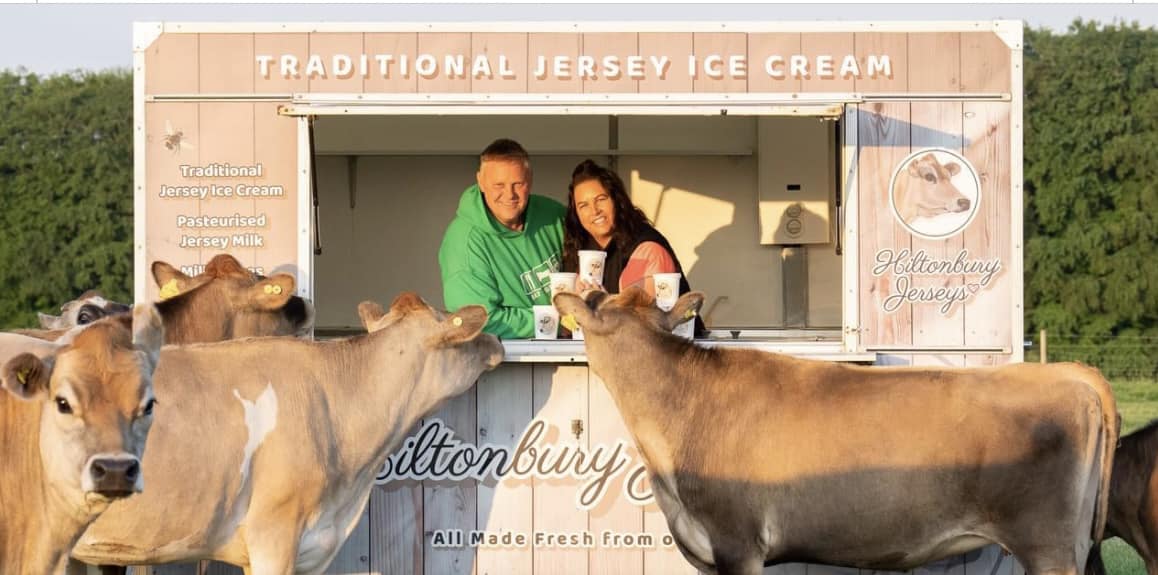

Over time, they’ve steadily expanded their offerings. Around 2019, they invested in a dedicated hygiene room and a second-hand ice cream machine, as well as a mobile ice cream trailer to supply events.

“We do about 18 flavours now,” said Oliver. “In summer, it flies out of the freezers.”

They’ve added their own Jersey beef boxes, fudge, raw milk soap made locally with their milk, and even equestrian supplies and country wear. Some customers spend just a few pounds, while others spend hundreds, but it all adds up, providing a stable, diversified income stream.

Connecting through events and social media

Hiltonbury Jerseys doesn’t just sell produce; they also share their story. “We’ve got about 25,000 followers on Facebook now,” said Oliver proudly.“People love seeing what we’re up to – milking, feeding calves, making ice cream, or even the odd tractor job.”

Videos and photos often rack up thousands of likes, proving there’s real appetite for understanding where food comes from. Events have become a key part of the farm’s identity.

“We’ve done food and craft festivals, bringing in 40 or 50 local producers. Last year, we reckon about 2,500 people turned up. We’ve got tractor rides, animals on display – the works”, he explained.

Shaleen orchestrates these events, which not only generate revenue but also help put the farm on the map and build connections with customers and other producers.

Environmental stewardship and herd management

Despite the focus on retail and events, Oliver hasn’t lost sight of traditional farming priorities. He works on free-draining, flinty, chalk soils, which lets him turn cows out relatively early, and he’s planted new hedgerows to encourage biodiversity.

The herd is managed with loose yards for better welfare and to produce valuable manure that’s spread back on fields, reducing artificial fertiliser use. He’s also introduced herbal leys and red clover to improve forage quality and cut down on fertiliser and bought-in protein.

“We’re always thinking about how to keep the system ticking over nicely without over-reliance on expensive inputs,” he added.

Oliver’s approach to grazing is simple and flexible. “I let them out as weather and conditions allow; they can come and go, find shelter if it rains, and I buffer feed them inside. It works for us,” he said.

Next generation

Oliver’s stepdaughter Cova looks after the calves, milks and helps with field work. Even her boyfriend Jamie chips in, having learned the skills needed to help with fieldwork when he’s not off carpentering.

“It’s a proper family farm,” Oliver said. “We don’t employ many people. Between us, we manage the cows, shop, fieldwork and events. We’re flat out, but it’s rewarding.”

This family involvement brings its own challenges, especially when it comes to getting a break. “When one of us wants a day off, the others cover. It’s tough, but we manage. Maybe in time we’ll take on a relief milker to take a bit of pressure off.”

Looking ahead – fewer cows and more diversification

With the infrastructure now in place, Oliver has been thinking about the future. The dairy system produces a lot of milk, but he dreams of scaling back cow numbers to 30 or 40 milkers while growing direct sales.

“Why milk 100 cows for a processor at a lower price, when I could milk fewer cows and add more value myself?” he asked.

Selling raw milk at £2.50 a litre directly to customers far outweighs the 50 pence per litre he might get wholesale. He’s open-minded about further diversification, too, thinking about perhaps adding glamping or more events to capitalise on the farm’s location and views over Winchester.

“We’ve just put in outside loos,” he said, before explaining that the family is in the process of looking into bell tents for the coming glamping season.

Reflections on the industry

Like many farmers, Oliver has seen the sector contract dramatically. “When I started, there were nearly 39,000 dairy farms. Now it’s around 6,000,” he said. “It’s tough. Costs are huge, and we’re not always paid what we deserve. But if you want control, you have to go direct.”

He appreciates the spotlight thrown on farming by programmes like Clarkson’s Farm. “We need public understanding,” he said. While he believes collective action could force fairer prices, he knows it’s easier said than done.

A hopeful vision

As I prepare to leave, a steady flow of customers continues. Some pick up milk and fudge, others browse the beef. All tell the same story – Hiltonbury Jerseys has found a winning formula by focusing on quality, transparency and building customer relationships.

Oliver and his family show how British dairy farms can thrive through direct sales, value-added products and strong community engagement. Here on the edge of Winchester, Hiltonbury Jerseys stands as a beacon of what’s possible.

Farm Facts

- 160-acre county council farm plus 35 rented acres and 25 acres for hay

- 120 Jersey cows (6,000 litres average yield), year-round calving

- Sexed semen plus Angus and Belgian Blue genetics for beef crosses

- 24:24 Dairy Master milking parlour

- Sells 400 litres raw and 400 litres pasteurised milk weekly direct to customers, with the remainder going to dairy processor

- Produces 18 flavours of Jersey ice cream on-site to sell from the shop and via a mobile ice cream trailer throughout the summer months

- Sells approximately one body of beef per week through the shop

- Over 25,000 Facebook followers

- Considering Sustainable Farming Incentive options

- Website: www.hiltonburyjerseys.co.uk

- Does all his own tractor work, including forage harvesting

- Cova milking

- Shaleen and Oliver

- Oliver Neagle, Shaleen Neagle, Cova Butcher and her boyfriend Jamie Bramble

For more like this, sign up for the FREE South East Farmer e-newsletter here and receive all the latest farming news, reviews and insight straight to your inbox.