This month, Nigel Akehurst visitsed Brodie Farms in Brockham, Surrey, to meet farmer-turned-biochar maker Alex Brodie, his son Tom and farm manager Andy Jackman. Together, they’re embarking on a pioneering venture, using biochar to radically improve their own soils and exploring a host of new opportunities.

Pulling up at Felton Farm on the outskirts of Brockham, I’m greeted by a very solid looking green sliding gate. After pressing the buzzer and parking opposite a sizeable modern barn, I meet Alex, Tom and Andy. It’s immediately clear this is more than your traditional farming operation.

A farm in transition

Standing outside the wood chip screening barn, farm manager Andy Jackman reflects on how the farm has changed in his 45 years with the family. Once they farmed the land in-house and even rented an additional 600 acres, running 1,700 commercial ewes alongside arable. By the late 1990s, farming margins were squeezed, prompting a shift.

In 2000, the Brodies launched a wood recycling business at Felton Farm, taking in logs, brash and wood chip from local tree surgeons, and let out a few barns. Over time, this diversification thrived. By 2015, Alex was researching how to move the business forward again.

“Most of our wood was being trucked north,” he explained, “some to be composted, some to landfill. It wasn’t an efficient use of resources.” Various feasibility studies followed, exploring renewable heat incentives and other ideas, yet the numbers never quite stacked up, until a consultant’s report in 2020 casually mentioned biochar.

What is biochar and why is it valuable?

For anyone unfamiliar with biochar, I asked Alex to explain it in simple terms. It is a carbon-rich material created when organic biomass, in this case wood chip, is heated in a low-oxygen environment (pyrolysis), he said. Whereas charcoal is made when wood is burned at between 200°C and 300°C, biochar is produced at 400°C or higher; Felton’s pyrolysis unit can reach up to 900°C.

The result is a stable product that can lock carbon into the soil for centuries, mitigating climate change. It also improves soil fertility by boosting nutrient retention, microbial activity and water-holding capacity (it can hold six to seven times its weight in water and release it when sodden, meaning it acts like a sponge), potentially lifting yields and reducing irrigation needs. Biochar can help curb greenhouse gas emissions like methane and nitrous oxide, while also providing a solution for forestry and agricultural waste.

Securing funding and facing down threats

Initially, Alex explored grant funding for the biochar plant but found it “wasn’t deemed innovative enough”. Equity funding also felt unsuitable, so he ultimately secured a green loan from his bank (HSBC). In his business plan, he tackled potential threats head-on:

- Supply of biomass: They’re well placed in one of England’s most wooded counties, with strong links to local tree surgeons.

- Reliability of technology: Alex and Andy visited their Welsh supplier, WoodTek Engineering, to see the Woodtek C1000 biochar system working first hand. Mick Jones has been engineering biochar production plants and farming using biochar since 2021. Since being commissioned in September 2024, the system has been operational 75% to 80% of the time, with a few minor issues that Mick and his team have either been able to troubleshoot remotely or have visited to sort out.

- Commercial market: The UK biochar market is still emerging, but Alex is optimistic. He’s collaborating with other small UK producers and selling to private horticultural clients via his website (www.broiebiomass.co.uk).

Elsewhere in the world, biochar adoption is more advanced. “In the US, farmers are already being paid to apply it to their fields,” Alex remarked, adding that Europe’s biochar market is also growing quickly and has been valued at an anticipated USD 2.71 billion by 2032.

Plant tour

As I was keen to see a bit more of the operation, Alex and Andy took me to the wood yard first, where local tree surgeons drop off wood chip, brash and logs, all stacked in large piles. The biochar plant consumes roughly 100 tonnes of wood chip a week. A JCB telehandler loads chip into a screener, segregating it into three streams; one fraction heads for pyrolysis, one for compost and anything too large goes back into the brash pile for further shredding.

Screening and drying: Wood chip is dried in the main barn until it reaches the correct moisture level and is then conveyed into a second shed where it is screened a second time before being collected by JCB to be transported to the next door shed for pyrolysis.

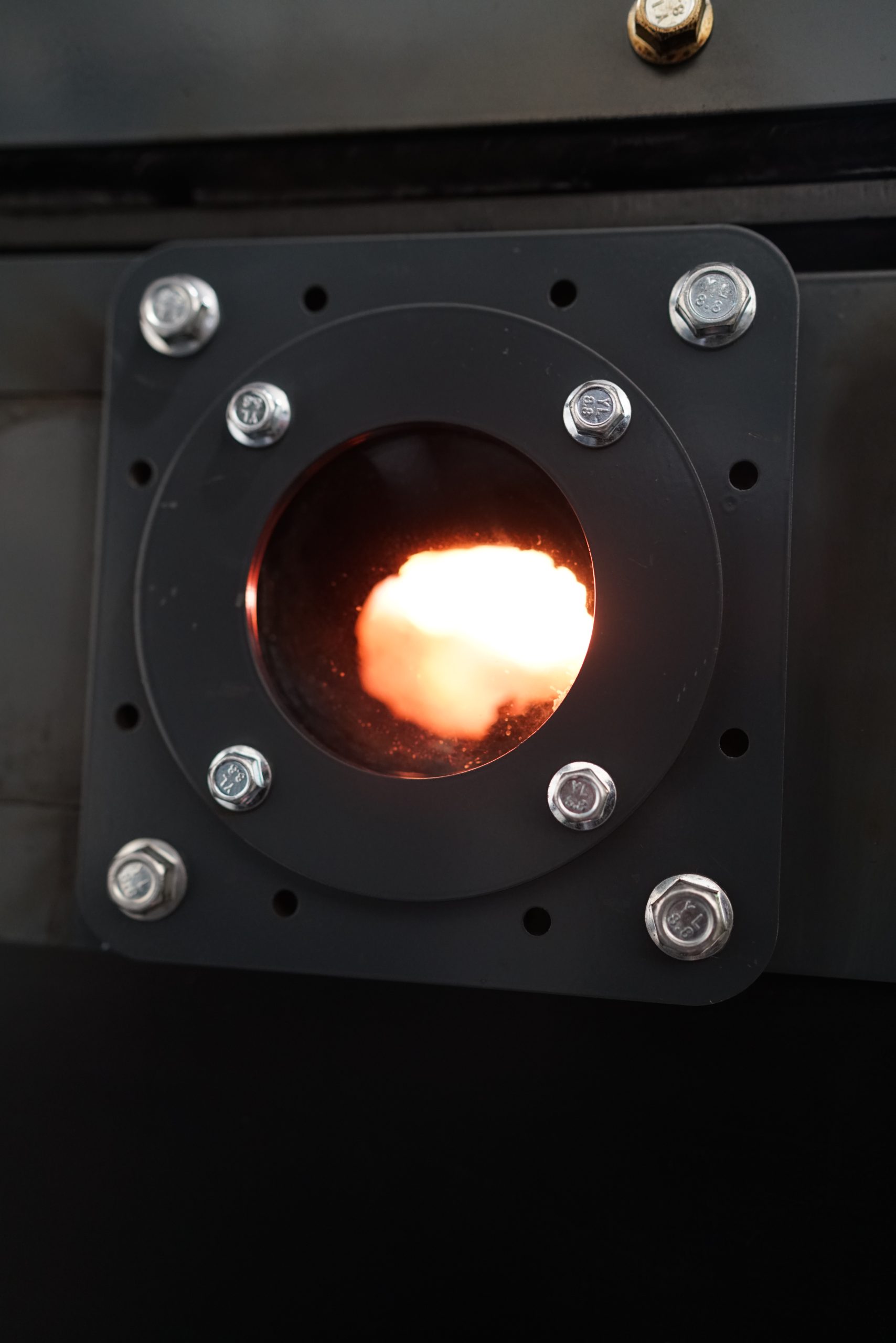

Pyrolysis in action: In the pyrolysis shed stands a tall, black, spaceship-like machine. Heated in a near-vacuum at over 800°C, the wood chip is transformed into biochar. Through a glass panel, I glimpsed the lower chamber where wood becomes biochar. Afterwards, the biochar is discharged into a neighbouring bay, ready for loading.

Future renewables: A final bay is reserved for an eventual renewable energy project; plans include generating electricity from the pyrolysis heat and potentially selling it back to the grid. The heat produced already heats the water which goes to the drying barn to dry both the wood chip and agricultural produce.

Mixing with compost and on-farm trials

Hopping into Alex’s pickup, we head to the compost yard a short drive away along a farm track. As we near the yard, he points out a 120m-long windrow (about 1,500 cubic metres) composed of biochar, compost and horse manure.

“You need to inoculate biochar with compost,” he explained. “On its own, biochar is inert, but when you mix it with compost, you populate the biochar’s pores with microbes and nutrients. This is what brings real benefits to the soil.”

He has taken baseline soil samples from Felton Farm’s arable land and plans to spread the compost/biochar mix this autumn. If the trial delivers higher yields, reduced input costs and elevated soil organic matter, Alex reckons they could see a net improvement of at least £60,000 to the bottom line.

In the compost yard, we inspect different piles of biochar and various windrows. Using a Compost Manager toolkit, Alex monitors temperature, oxygen and other variables, accessing data securely in the cloud and turning the piles at optimal times.

Livestock benefits

Biochar isn’t beneficial only to arable farmers; livestock could also reap rewards from it, explained Alex. Studies suggest that, when used as a feed additive, biochar’s high absorbency can suppress gut pathogens and improve overall digestive health, leading to better feed efficiency and weight gain.

It can also bind nutrients in manure, creating a nutrient-dense compost/fertiliser product that might replace petroleum-based fertilisers, cut odours, and generate new income streams for farmers. Similar benefits apply to the poultry market. As a peat-free compost, it is also of interest to the horticultural market and vineyards.

Carbon sequestration and credits

With the global carbon market in a boom, Alex is finalising the life cycle analysis of his biochar operation and aims to sell carbon credits soon. Each tonne of biochar represents around 2.5 tonnes of CO₂ sequestered, which is worth 2.5 carbon credits.

“After brokerage fees, that’s roughly £150 per tonne of biochar produced,” he said. Producing 2.5 tonnes of biochar daily, his annual target of 900 tonnes could yield 2,250 credits—enough to make a substantial dent in the plant’s financing costs.

Beyond agriculture

Beyond farms, other industries are taking notice. Alex has sold biochar to horticultural clients in one-tonne bags priced at £600, while exploring larger bulk deals.

At the recent Bio360 Expo in Nates, France, he found a company using biochar for 3D printing, valuing it at £3,000 per tonne. Asphalt and cement companies are interested, as are brick manufacturers, who see its potential as a coal substitute for colouring bricks. As an alternative to activated charcoal, biochar can also be used in water filtration systems and for land remediation.

Looking ahead

Back at the main yard, Alex hands me more information on biochar. I ask for his ultimate vision. He references Terra Preta (by Ute Scheub, Kaiko Pieplow, Hans-Peter Schmidt and Kathleen Draper), a seminal work that has fueled the recent surge of interest in biochar: “If we, by means of climate farming, were to raise the humus content of soil by 10% within the next 50 years, the carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere could potentially be reduced to preindustrial levels.”

Adding biochar to the soil, Alex believes, is one key piece of a much bigger puzzle. However, he’s convinced it can be transformative, not just for Brodie Farms but for agriculture, the environment and beyond. He’s eager to prove the concept through his on-farm trials, share his experiences and watch this pioneering project flourish in the years ahead.

Farm facts

- Just under 550 acres across three farms, including 474 acres of arable (contract-farmed by Ford Farms), 62 acres of woodland and 52 acres of grass, grazed by Tom’s polo ponies

- Diversification: A 25-year wood business at Felton Farm, commercial lets and a new biochar plant

- Under a Countryside Stewardship mid-tier agreement

- Biochar trial: Baseline readings taken on arable land at Felton Farm for on-farm compost and biochar experiments

- Plant capacity: Consumes 100 tonnes of wood chip weekly, producing 17.5 tonnes of biochar

- Biochar is recognised by the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC) as a form of carbon sequestration and therefore generates carbon credits which can be sold

- It also increases soil organic matter and displaces the need for chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

- default

- default

- Andy, Alex and Tom

For more like this, sign up for the FREE South East Farmer e-newsletter here and receive all the latest farming news, reviews and insight straight to your inbox.