Last month I took a picture of our sheepdogs driving lambs down the lane. What I failed to reveal is that three lambs had climbed the high bank, feasting on ivy, and were hidden from view. None of the moving team noticed. We turned the lambs into the home field and shut the gate, congratulating ourselves on a smooth operation.

Our triumph was short-lived. We were alerted to our mistake and promptly reassembled to round up the escapees. These lambs, however, having tasted a brief spell of freedom, had other ideas. ‘Uncooperative’ is an understatement; they were wild, and embarrassingly managed to flatten a passing motorist who had stopped to help. Eventually they found a gap in the hedge and escaped onto neighbouring land. Deciding it was best to let them calm down, we retreated.

By the next day these lambs had returned to the original pasture they’d been grazing. We nicknamed them “the feral lambs”. While we managed to shut them in a paddock, getting near them was another matter. They were fast and agile, effortlessly clearing sheep hurdles. It took weeks of coaxing them with feed before we finally secured them in a trailer and returned them home. According to the landowners who witnessed our struggles, it was “better entertainment than Netflix”.

Sometimes mundane farming tasks turn into far more adventure than we’d like. For example, my recent experience checking the marsh flock. The ewes needed new grazing, so I called them to follow me towards the gate. Suddenly, I felt an impact from behind, a force so strong it ricocheted up my spine and sent me sprawling face first into a heap on the ground.

I looked up to see a menacing ram bearing down on me for round two. Thankfully I’d held onto my crook, (which I carry in case I need to rescue sheep from the dyke). I used it to fend off my attacker. I knew I should have removed the rams sooner. Ungrateful brute, he had better sire some descent lambs or he’ll be heading to market. Now I always take a dog as backup.

A few days later, winter calving began, a time when newly calved cows can be notoriously tetchy. The fifth cow to calve was mothering her calf who would keep sucking on the side of the teat, consequently getting hungry and disillusioned. To help, we decided to feed the cow while assisting the calf with its connection technique.

My other half was supervising this while I was behind preventing it from backing away. Unfortunately, we underestimated how quickly the cow would finish her food. She turned, spotted me and charged. I wasn’t quick enough, she knocked my head against the hurdle and blood streamed down my neck and face. I didn’t hang about.

In hindsight we should have put a halter on the cow, but it was late and we were focused on ensuring the calf got its colostrum. At least we succeeded; the calf finally clued up. As for me, I cleaned up my two head gashes and applied pressure until the bleeding eased. Against family advice I stayed home rather than seek medical attention. It’s sore but it’s healing. Lesson learned: err on the side of caution next time.

Winter calving is now successfully completed. Notably, a 13 year-old British blue calved naturally, producing a pair of robust twins. She had us worried post calving because she became lethargic and lost her appetite. Her temperature was normal, and she continued to drink water. We tried tempting her with a range of enticing foods with little success. We consulted the vet, who suggested giving Metacam and Betamox, and we also gave her a mineral bolus. Five days later the cow perked up, returning to normal behaviour. Perhaps the twins were a shock to her system.

I enjoy the start of a new year, opening up a fresh diary, new plans, and the hope that 2025 will bring better things. Early January saw us undergo a Red Tractor inspection. If we didn’t sell some cattle to ABP or Dunbia, I’d gladly forego this exercise. The paperwork, writing down the reason for giving each medication, is infuriating. The tick box side of today’s farming is endured, not enjoyed. Bureaucracy is strangling UK business growth. According to celebrity farmer Gareth Wyn Jones, it costs

£155 million annually to run DEFRA.

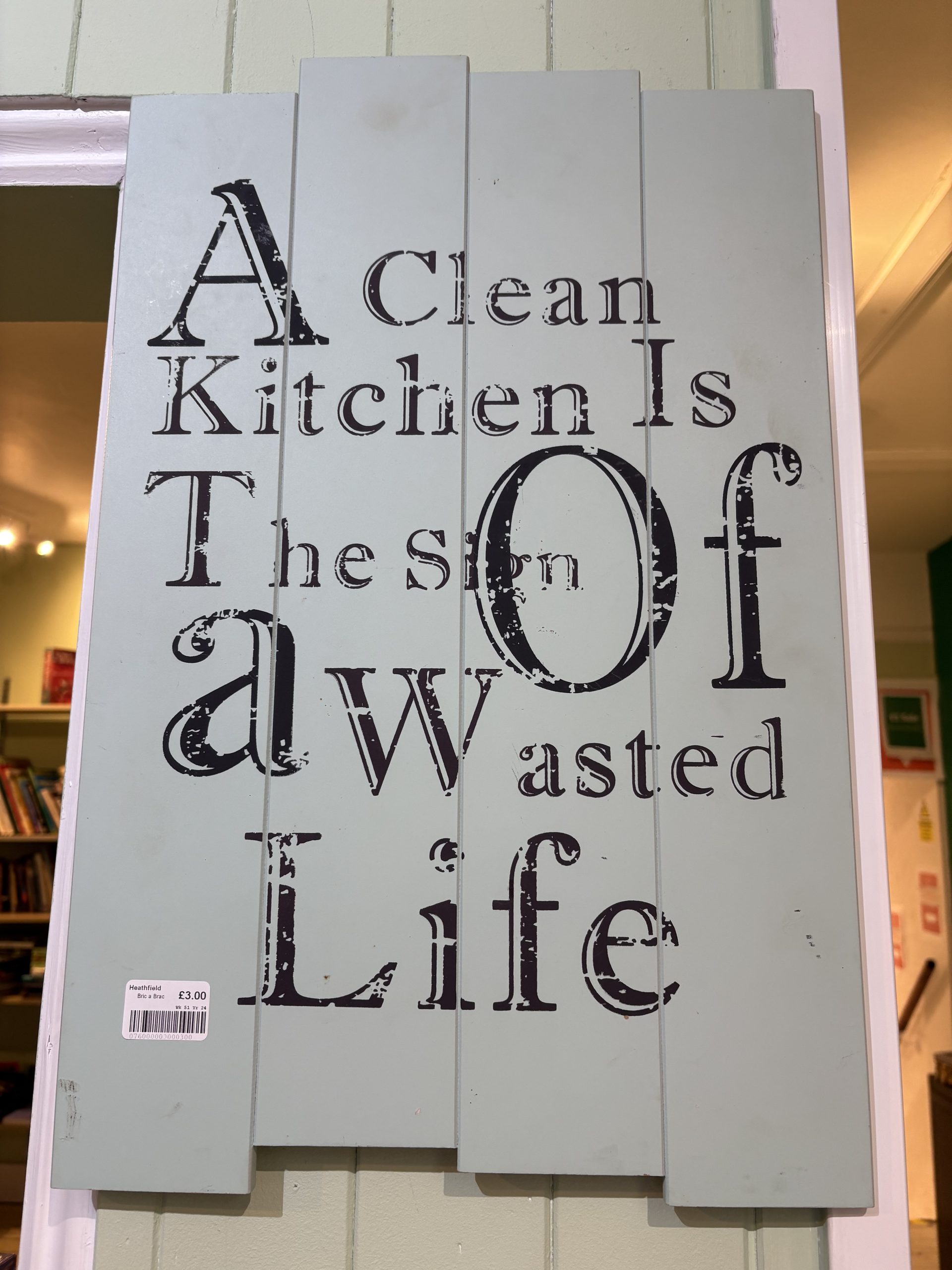

Our kitchen table seems to act as a magnet for an assortment of clutter; paperwork, files, keys, cakes, plates, cups and more. Over Christmas my brother popped in for a visit. As he sipped his tea, he surveyed the chaos and commented: “Your column is called

At the kitchen table, but I’ve never actually seen your table.” Harsh, but fair; classic sibling banter. I didn’t confess that I’d been tempted to buy a plaque that read: A clean kitchen is a sign of a wasted life.

For 2025 my resolutions are positive thinking and a clear kitchen table.

On a successful note, have you heard of Fresh Start for Hens? With only one hen left and no luck finding point-of-lay pullets, it was suggested I try the above charity. Although initially I was sceptical, as it’s all done via emails and I worry about online scams. I donated the £2.75 per hen requested. A few days later I was told I could collect my six hens from a housing estate in Hailsham. These hens settled in beautifully, and yesterday I collected six eggs. I’m thrilled.

We’ve just enjoyed a brief spell of frosty nights and glorious sunny days. The golden sunrises have been stunning. Of course, the freezing temperatures cause associated problems, like frozen pipes and troughs, tractors needing extra cosseting to get started, icy patches to be wary of etc., but its preferable to wet, murky, mud-making weather and the bonus is that dogs stay clean. That said, swans sliding along on top of the frozen dykes are less happy. Hopefully the cold will lower the bluetongue risk and kill off other unwanted bugs and parasites.

The first day of February marked the end of the pheasant shooting season. My daughter’s terrier, our spaniels and I thoroughly enjoyed being a part of this community.

- Being part of the shooting/ beating community is fun

- Swans walking along frozen dykes

- Chilly but bright

- Waiting in the woods, before we start work

- The feral lambs

- Playing hard to get

- So nearly in the pen, but we can jump !

- Tempted but refrained from getting this

- Ouchy

- Brie now acts as my protector

- Frosty sunrise

- Getting cosy in the bedding

- Ice this depth is a rare sight these days

For more like this, sign up for the FREE South East Farmer e-newsletter here and receive all the latest farming news, reviews and insight straight to your inbox.