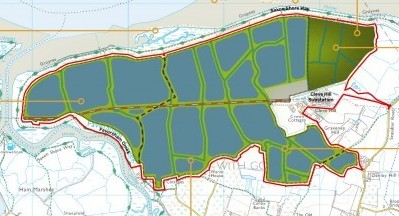

Cleve Hill Solar Park Ltd is proposing to build the park on 1,005 acres of farmland near the River Swale, between Faversham and Seasalter.

The company has already held one consultation in December, and is planning another. Because of the project’s colossal size, its planning won’t be considered in the usual way by local authorities. Instead, an application for a development consent order is expected to be submitted to the planning inspectorate in May: they will have 28 days to review the application and decide whether or not to accept it.

As the park will probably generate more than 50 megawatts, it is classified as a nationally significant infrastructure project and will be determined by Greg Clark, secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy.

Reaction to the plans has been mixed, with no one questioning the need for renewable energy power stations to replace those run on fossil fuel. “We are not against renewable energy but this particular location is quite sensitive,” said Greg Hitchcock, Thames Gateway officer for Kent Wildlife Trust. “We have never seen something of this scale in this country before and the new design leaves some questions unanswered.”

Mr Hitchcock explained that rather than the solar panels facing south, they will face east and west, so they could be installed closer together. This could decrease vegetation growth and allow more run off from the site into surrounding ditches which are home to water voles, reed bunting and other species.

At certain times, the site does support species which are important in surrounding habitats. “The developer will have to undertake a habitats regulations assessment to determine the impacts on the species and what mitigation may be necessary,” Mr Hitchcock explained.

South East Farmer approached Cleve Hill Solar Park to ask whether such a large amount of farmland should be used for renewable energy rather than food production, but the company did not return our call. Local planning authorities can use the agricultural land classification (ALC) system to make decisions about the appropriate development of land. This aims to protect the best and most versatile land (BMV) from significant development.

The ALC is graded from one to five, and the BMV land is graded one to 3A. Most of the land at the Cleve Hill site is classified as grade 3b farmland and so falls outside the BMV grades: there is also a small area of grade two. DEFRA’s guide for assessing development proposals on farmland says grade 3b is “moderate quality agricultural land” which can produce moderate yields of a narrow range of crops such as cereals and grass

Land registry records show most of the site is owned by Martin, Charles and Robert Goodman, who are based at Home Farm, Eastwell Park in Kent. The land is subject to an option agreement in favour of Cleve Hill Solar Park Ltd, and a scoping study prepared for the development says: “It is generally accepted that where ground mounted solar photovoltaics (PV) developments are proposed to be sited on agricultural land, it should be demonstrated that poorer quality land is used in preference to higher quality, and that options are explored for continued agriculture use.

“It is not currently known how the land will be managed under and around the solar PV modules (but) there is potential for continued agricultural use of the land through grazing.”

If the park is built, the company says it could generate more than 350 megawatts – enough for roughly 110,000 homes a year, which is about the number of households in the Swale and Canterbury districts combined.

The park could bring £27.25 million investment to Swale and Kent over a minimum period of 25 years. “Based on current estimates of the potential generation capacity, the revenue generated for Kent and Swale councils will be in excess of £1 million,” the company added.

Role for farmers in giant solar projects

NFU chief adviser on renewable energy Dr Jonathan Scurlock said he was “not entirely surprised” by the Cleve Hill application.

“We know full well what a roller coaster ride the solar industry has been on in the last seven years. As the cost of the kit comes down, it becomes ever more pressing to put solar panels on roofs or agricultural land because we need clean energy.”

Since the government stopped subsidising solar, projects such as Cleve Hill inevitably depend on private finance and need economies of scale to recoup the cost of their investment, said Dr Scurlock.

For solar projects valued at up to roughly £1 million, there is a big attraction for farmers: they can put up some of the money, borrow the rest and then own the asset. They can meet their own energy needs and export the rest of the power into the grid. For much bigger projects developed by third parties – such as the Cleve Hill one – Dr Scurlock said there is a role for the landowner to receive a ground rent for the panels, while using the land for biodiversity measures and charging for grazing services with sheep.

“The other thing starting to happen with solar farm projects is the addition of battery storage,” Dr Scurlock said. This is proposed for Cleve Hill, and Dr Scurlock said the batteries can be charged up during the day and spread the use of power into the evening peak and the night. “Battery storage can also mean connecting more power on a limited grid connection – not all the power needs to be exported at the same time.”

The NFU, said Dr Scurlock, would not be “overly concerned” by the Cleve Hill development if it was in line with the best practice codes developed by farmers’ representatives and the solar industry previously for much smaller solar farms. There are about 1,250 solar farms in the UK, and most are on farmland. In 2011, when solar farms were first introduced, they were about five megawatts (MWs) in size on 25 acres. Today, there are about 750 smaller farms under five MWs, 400 odd farms between five and 25 MWs, and 40 projects over 25. The second largest after Cleve Hill is a proposed 120 MW farm near Scunthorpe.

Pitching the solar panels to face from east to west rather than to the south has not been tried on any scale in land based projects so far. There is a hypothetical risk, said Dr Scurlock, that Cleve Hill – which is proposing the east/west layout – could harm the “high public approval rating of solar power so far”.

“Imagine the casual dog walker who may at first find the panels in a solar farm look a bit alien. But if such a visitor could see butterflies, birds and sheep among them, he or she might conclude they were a remarkably good multi-purpose use of land. If, on the other hand, the occasional visitor was confronted with hundreds of metres of bare soil created by the east/west facing panels – plus a man walking round with a back pack sprayer to control weeds – that would not create a very favourable impression.”